Studio Ghibli and a growing number of Japanese content creators are urging OpenAI to stop using their copyrighted material for AI training. Last week, the Content Overseas Distribution Association (CODA), which represents major publishers and studios including Studio Ghibli, sent an open letter demanding that OpenAI halt the unauthorized use of their creative works in training large language and image models.

Studio Ghibli, the world-renowned animation studio behind Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro, has been among the most visibly affected. Since OpenAI released its image generator in March, social media users have flooded platforms with “Ghibli-style” selfies and pet portraits. Even OpenAI CEO Sam Altman joined the trend, updating his profile picture on X with an AI-generated “Ghiblified” version of himself.

Now, with OpenAI’s Sora video generator expanding access, Japanese publishers say the problem is escalating. CODA’s letter insists that the company refrain from using its members’ films, artwork, and creative material in any form of machine learning without prior consent.

OpenAI has long followed an “ask forgiveness, not permission” approach to copyrighted data, a stance that has sparked backlash worldwide. Its products allow users to create AI-generated content in the likeness of copyrighted characters or even deceased public figures. That policy has already drawn criticism from organizations like Nintendo and the estate of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., both of which have voiced concern over unauthorized deepfakes and derivative works.

In its statement, CODA argued that OpenAI’s practices could constitute copyright infringement under Japanese law. “When specific copyrighted works are reproduced or similarly generated as outputs, the act of replication during the machine learning process may constitute copyright infringement,” the association said. Unlike U.S. copyright law, Japan’s system requires prior permission to use copyrighted material, with no mechanism for retroactive objection.

This legal distinction may prove critical. While a U.S. federal court recently ruled that AI startup Anthropic did not break copyright law by training on copyrighted books, the same act might not be permissible under Japan’s stricter framework.

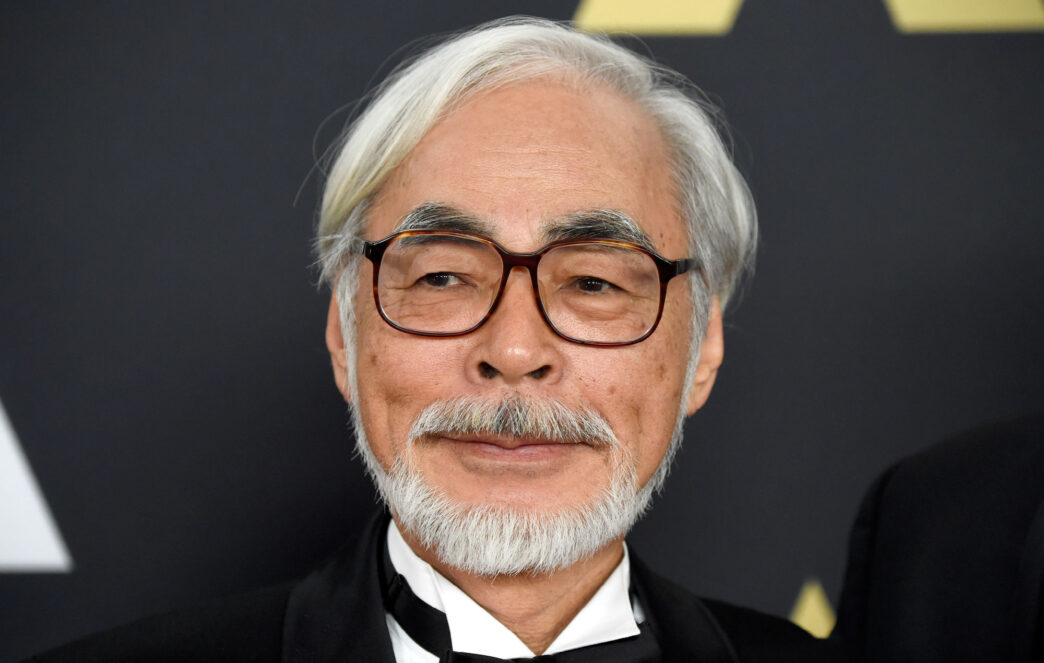

Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki has long been vocal about his disdain for artificial intelligence in art. In 2016, after being shown an AI-generated animation prototype, he called the work “utterly disgusting” and “an insult to life itself.” Though he hasn’t commented directly on the recent wave of AI-generated Ghibli imitations, his earlier stance reflects the studio’s deep-rooted philosophy that art must stem from human experience, empathy, and craft, not algorithms.

As the legal debate continues, OpenAI faces increasing global pressure to redefine how it sources creative material for training. For Japan’s animation houses and publishers, the issue is not just about copyright, it’s about preserving the integrity of human artistry in the face of synthetic reproduction.