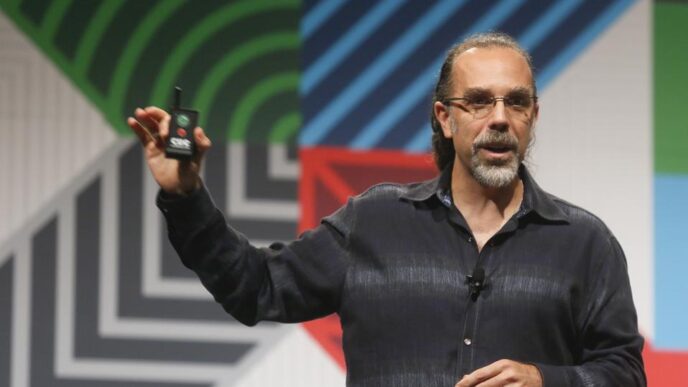

Kevin Rose, a general partner at True Ventures, has a simple, almost comical rule for deciding whether to back an AI hardware startup: If you’d want to punch someone in the face for wearing it, don’t invest. It’s blunt, but it perfectly captures his skepticism about Silicon Valley’s latest obsession, AI-powered wearables that listen, record, and analyze everything around them.

Rose, a general partner at True Ventures and early investor in Peloton, Ring, and Fitbit, has watched enough hype cycles to spot trouble early. While the industry scrambles to fund AI-powered glasses, pendants, and pins, he’s staying on the sidelines. His concern isn’t just about functionality, it’s about how these devices make people feel.

“Most of these products break basic human norms around privacy,” Rose said at a recent event. “They’re designed to listen to entire conversations, and that’s not how people want to live.”

Rose knows the wearable market well. He served on the board of Oura, the Finnish company that dominates the smart ring category with over 80% market share. That experience taught him a hard truth, the most successful wearables aren’t just technically impressive; they’re socially acceptable. “You have to ask how it makes others feel when you wear it,” he explained. “Cool tech isn’t enough if it creeps people out.”

He’s tried several AI wearables himself, including the much-hyped Humane AI Pin, which briefly became a viral sensation before fading into infamy. The novelty ended for Rose after one awkward argument with his wife. He found himself scrolling through AI logs to prove he was right. “That was it,” he said. “If you’re using your AI pin to win an argument, it’s time to take it off.”

For Rose, these stories highlight a deeper problem, AI hardware is losing touch with emotion and humanity. “We keep adding AI to everything like it’s seasoning,” he said. “We’ll erase backgrounds, replace skies, or delete gates from photos, and we call it progress. But it’s also rewriting memories. One of my friends literally erased a gate from his yard photo. I told him, ‘Your kids will look at that someday and wonder where it went.’”

That uneasy feeling, Rose said, mirrors the early days of social media, full of excitement, blind spots, and unintended consequences. “We thought connecting everyone was a great idea,” he said. “Then a decade later, we realized how much harm it caused. We’re at the same moment now with AI.”

He’s experiencing those challenges at home too. Recently, his kids saw a video of him created with OpenAI’s video model Sora, featuring a group of Labradoodle puppies that didn’t exist. “They asked where they could get those puppies,” he recalled. “I had to explain that they weren’t real, that it was just movie magic. It’s a weird conversation to have with your kids.”

Yet despite his caution, Rose is far from anti-AI. He’s deeply optimistic about the ways artificial intelligence is transforming entrepreneurship and lowering barriers for new founders. “The tools are unbelievable,” he said. “A friend of mine built and deployed a complete app during a drive from LA to San Francisco. Six months ago, that would’ve taken a full team and weeks of debugging.”

He believes this pace of progress will only accelerate. “When Google’s Gemini 3 launches, errors will drop close to zero,” he predicted. “High school coding classes won’t even be about code anymore, they’ll be about vibe coding. The next billion-dollar startup could come from a teenager in a classroom.”

That shift, Rose argued, will fundamentally change venture capital itself. Founders no longer need massive teams or early funding to build powerful products. Many can delay fundraising, or skip it entirely. “It’s going to reshape VC, and in a good way,” he said.

While some firms react by hiring armies of in-house engineers, Rose sees a different future for investors. “The next generation of VCs won’t win on technical talent,” he said. “They’ll win on emotional intelligence. Founders will need empathy, mentorship, and people who’ve been around long enough to understand the human side of building companies.”

He believes successful VCs will be the ones who can stay consistent, not the ones chasing trends. “Founders don’t want fly-by-night investors,” he said. “They want someone who’s been through the chaos before and can stay calm when things break.”

When it comes to what he actually looks for in founders, Rose draws inspiration from Larry Page, who once told him that the best entrepreneurs have a “healthy disregard for the impossible.” Rose looks for that same spark, founders swinging for the fences, willing to take big, weird bets. “If everyone says it’s a terrible idea, that’s usually the one I’m most interested in,” he said. “Even if it fails, we back them again because the thinking behind it matters.”

In a world where AI is being bolted onto everything, from photo filters to fridge magnets, Rose’s advice sounds refreshingly grounded. Build things that make people feel good, not uncomfortable. Solve problems that matter. And before investing in an AI gadget, maybe ask yourself: Would you want to punch someone in the face for wearing it?